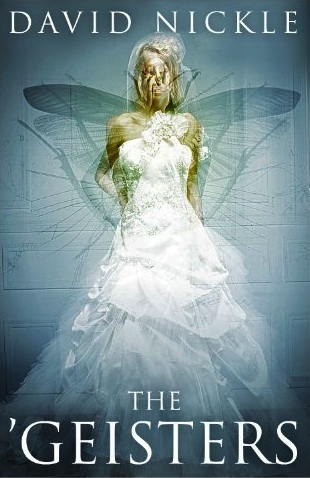

Check out David Nickle’s The ’Geisters, available now from ChiZine:

When Ann LeSage was a little girl, she had an invisible friend: a poltergeist, that spoke to her with flying knives and howling winds. She called it the Insect. And with a little professional help, she contained it. And the nightmare was over, at least for a time. But the nightmare never truly ended. As Ann grew from girl into young woman, the Insect grew with her. It became more than terrifying. It became a thing of murder. Now, as she embarks on a new life married to successful young lawyer, Michael Voors, Ann believes that she finally has the Insect under control. But there are others vying to take that control away from her. They may not know exactly what they’re dealing with, but they know they want it. They are the ’Geisters. And in pursuing their own perverse dream, they risk spawning the most terrible nightmare of all.

A Glass of Gewürztraminer

i

Was it terror, or was it love? It would be a long time before Ann LeSage could decide. For most of her life, the two feelings were so similar as to be indistinguishable.

It was easy to mix them up.

ii

“Family, now . . . family is far away,” said Michael Voors, and as he said it—perhaps because of the way he said it—Ann felt a pang, a prescience, that something was not right with him. That perhaps she should leave now. Until that moment, she’d thought the lawyer with the little-boy eyes was the perfect date: perfect, at least, by her particular and admittedly peculiar standards.

To look at, Michael was a just-so fellow: athletic, though not ostentatiously so; taller than she, but only by a few inches; dirty blond hair, not exactly a mop of it, but thick enough in his early thirties that it would probably stay put until his forties at least. He’d listened, asked questions—the whole time regarding Ann steadily, and with confidence.

Steadiness and confidence were first among the things Ann found attractive in Michael, from the night of the book launch. He’d approached her, holding her boss’s anthology of architectural essays, Suburban Flights, and asked her: “Is it any good?” and she’d said: “It’s any good,” and turned away.

He hadn’t been thrown off his game.

She had been enchanted by this easy confidence. After everything that had happened in her life—everything that had formed her—it was a quality that she discovered she craved.

But now, that confidence crumbled, leaving a man that seemed . . . older. And somehow . . . not right.

It hadn’t taken much. Just the simple act of asking: “What about you? Where’s your family from?”

He tapped his fingers and looked away. His suddenly fidgeting hands cast about and found the saltshaker, a little crystal globe the size of a ping-pong ball. His eyes were momentarily lost too, blinking away from Ann and looking out the window of the 54thfloor view of Toronto’s financial district, a high hall of mirrors up the canyon of Bay Street. They were in Canoe, a popular spot for lunch and cocktails among the better-paid canyon dwellers. It should have been home turf for him.

“Just my father now. In Pretoria. But—” and he twirled the nearspherical glass saltshaker, so it spun like a fat little dancer “—I don’t hear from him. We have had—you might say a falling out.”

“A falling out?”

“We are very different men.”

Their waiter slowed as he passed the table, took in Michael’s low-grade agitation and met Ann’s eye just an instant before granting the tiniest, most commiserative of nods: Poor you.

He picked up his pace toward the party of traders clustered at the next table, and Ann suppressed a smile. She was sorely tempted to stop him and order a big, boozy cocktail. But it was early—in the day, and in the relationship—for that kind of thing. Particularly because the way things were going, she didn’t think she’d stop at one.

“He is an Afrikaner,” continued Michael. “You understand? Not just by birth. By allegiance. When the ANC won the elections in 1994 . . . He wasn’t a bigot—isn’t a bigot, I mean. But he’d seen the things that the African National Congress could do—the business with the tires . . .”

“The tires?” Ann said, after a heartbeat.

Now Michael made a half-wise smile, set the saltshaker aside. His hand must have been trembling: the shaker kept rocking.

“My God,” he said, “you’d think I’d been into the wine already. I’m sorry. They would put tires around fellows they thought were traitors, and light them on fire, and watch them burn to death in the streets of Soweto. And then they became the government. You can imagine how he felt.”

“I remember that,” said Ann. She nodded in sympathy. That was real terror, now. In the face of it, her own inexplicable instant of fear vanished. “I was small. But didn’t Nelson Mandela have something to do with that?”

“His wife. Winnie. Maybe. Probably. Who knows?”

Ann smiled reassuringly and they sat quiet a moment; just the chatter in the restaurant, a burst of boozy mirth from the day traders; the pool-hall swirling of the saltshaker on the glass tabletop.

The waiter scudded near and inquired: “Need a minute?”

“Just a minute,” she said, looking at her menu.

Michael studied his too, and without looking up, said: “Share an appetizer?”

“Is there real truffle in the wild mushroom soup?”

“You want to share soup?”

“Is there a law says I can’t?”

That, thought Ann as she regarded Michael, was how you kept it going on a second date: make a little joke about the appetizer. Don’t talk international politics. For that matter, don’t start asking a lot of questions about how international politics and tires kept father and son apart for so long.

In fact, don’t start talking about family at all. Because as grim as the tale of Michael Voors’ own family turmoils might be— if Michael then started asking after the LeSages, and she was compelled to tell that horrific story . . .

Well. He was already thrown enough to fidget—she could hear the rolling sound of the saltshaker again.

“What about the salmon tartar?” she asked before he could answer. She allowed herself a smirk: why, Mr. Voors was actually blushing! “We don’t have to share soup.”

“No, I—” he was frowning now, and looking down at the table. “My goodness,” he said softly.

“What is it?”

Ann lowered the menu, and looked down at the table. And froze.

The saltshaker was dancing.

It twirled in a slow loop across Michael’s place setting, rolling along the edge where the curve met its base. Then it rocked, clicking as the base touched the tabletop, and rocked the other side, turning back. Michael held his menu in his left hand—his right was splayed on the tabletop near the fork. His pale cheeks were bright red as he stared. First at the saltshaker, then up at Ann.

“Isn’t that incredible?”

Michael set the menu down, well away from the perambulating saltshaker.

“Incredible,” said Ann quietly, not taking her eyes off the shaker as it continued to rock.

The Insect, she thought, horrified.

It was back.

No, not back.

Really, it had never left.

Ann wanted to reach out—grab the shaker in her fist, stop it physically. But she knew better. Already, she could hear the rattling of glasses at the long bar. Two tables down, one of the traders commented that the air-conditioning must have kicked in. One of his lunch-mates asked him if he were a woman and everyone laughed. Michael’s eyes were wide as he watched the saltshaker.

Ann reached under her chair and lifted her handbag. “Don’t touch it,” she said.

He looked at her and asked, “Why not?”

“I’m going to the ladies room,” she said and stood. “Now please— don’t touch it.”

Ann drew a long breath, and pushed her chair back to the table. Michael didn’t stop her, and he didn’t try to touch the spinning saltshaker either.

Their waiter, carrying a tray of two martinis and a fluted glass of lager, stepped past her—and without her having to ask, directed her with a free hand to the restrooms. “You have to go outside,” he said. “By the elevators. Just past them.”

Ann smiled politely and, shoulders only slightly hunched, head bowed only the tiniest, hurried between the tables, out the doorway and past the elevators—and there to the women’s washroom where she finally skulked inside. It was as safe there as anywhere, now.

One blessing: the washroom was empty but for her. She made her way to a sink, spared herself a glance in the tall, gilt-framed mirror. Her makeup was holding. That was something.

Ann fumbled with her phone.

It was a new one, and she hadn’t had time to program her numbers into it. Not a catastrophe—she knew the number she had to call now like she knew her own name—but speed dial would have helped.

Finally, a signal. One ring.

Would the glasses still be on the rack now, or sliding, one by one, along the rails, crashing into the plate glass windows overlooking Bay Street?

Two rings.

Would frost be forming around the edges of those windows, irising a circle of white, evil crystals to block out the sun?

Three.

Would one of the traders hold up his hand, wonderingly, examining the steak knife that had penetrated the back of it as he sat, turning it this way and that while his mind processed the impossibility of it, and itself began to unravel?

Four.

The first might be dead—the only question would be who . . . who it would choose. Not the waiter! Not Michael Voors—

Oh God . . .

“Come on, Eva,” Ann said to the empty washroom. “I need you.”

And click: and five. And . . .

“Hello?”

“Eva!”

“Ann?” Eva Fenshaw was on her own cell phone—she’d obviously figured out the intricacies of call-forwarding since last they spoke—and her voice crackled. She sounded as though she might be in some large space—maybe the Wal-Mart where she liked to spend hot afternoons before her consultations started in the early evening. Ann should have remembered, and called the cell phone first. “Ann, how nice to hear from you!”

“Not so nice, Eva,” said Ann.

“Are you all right?” Pause. “Ann, dear?”

“It’s coming,” said Ann.

“Oh oh. The Insect.”

“The Insect.”

“Oh.”

The acoustics shifted—maybe as Eva moved down an aisle, someplace more private. “All right, Ann. It’s all right.”

“It’s not all right. It’s back, it’s coming out, I can feel it.”

“Where are you? At work?”

“At lunch. With a date.”

“With that Michael?”

“Michael Voors.”

“Dear Creator,” Eva whispered. She had, of course, warned Ann about Michael; Eva Fenshaw had a lifelong distrust of lawyers, born of the needless troubles in her divorce thirty years ago. When Ann told her about Michael’s interest in her, Eva had had some unkind things to say.

She didn’t repeat them in the Wal-Mart. “All right, Ann. Were you drinking?”

“God no.”

“Good. Now. How did it manifest?”

“The saltshaker,” said Ann. “Moved on its own. That’s for sure.”

“In the restaurant.”

“In the restaurant!”

“Telekinetically.”

“Yes!”

“Don’t shout,” said Eva. “Stay calm. We’re going to visualize the safe place.”

Eva gave a yogic huff, and Ann drew a deep breath.

“It hates him,” she said. “It’s the same as before.”

“Ann!” Her voice was sharp this time. “Visualize the safe place, Ann. It can’t harm you there. And if it can’t harm you . . .”

“I can control it. All right.” She shut her eyes.

“Good, dear,” said Eva, in a voice that seemed to recede down the long corridor that was the first part—the gateway to Ann’s safe place. Eva had helped her construct it—how long ago? Not important. Ten years ago. At the hospital. You remember the hospital, don’t you, little Annie? I know I do—

Ann concentrated on opening herself up, seeing the hallway, walls made of cut stone with bright, leaded glass windows along both sides. There was a sunrise—Ann was always happier with the onset of light than she was the spread of darkness—and it manifested in pinkish rectangles along the flagstone floor.

The safe room was at the far end of the corridor. It would take a moment to walk, but by the time she had made the journey, she would have shed the tension that had brought her here. That was how Eva had explained it, all those years ago as they sat together in the lounge in Fenlan, waiting for word of her brother, of Philip after the crash.

“You’re going to walk as slowly as you need to, and at each window, you can pause and throw any worry you have out there into the light.”

“Light of the rising sun?” young Ann had asked, and Eva had replied: “Just the light.” And she had held Ann as Ann described how that hallway would be: like the hallway between high towers in a wizard’s castle.

The wizard wasn’t there, because she was the wizard.

This was Ann’s castle.

She stopped at the first window. Ann always had a leather satchel with her when she walked the Hall of Light, and she reached into it this time. She found a small parcel, wrapped in a dark, oily cloth. It was warm to the touch.

It wasn’t important—it might even be counterproductive— to try and determine what worry, exactly, was contained in this package. Whatever it was, it was heavy, and warm, and alive. She pushed open the first window, and threw the package out. It fell into the hot sunlight, down the mountainside, and disappeared.

She was inclined to hurry, to the thick oak door at the far end of the hallway. She certainly could do so; the castle existed only in her imagination, as guided by Eva’s own counsel. She could simply imagine herself all the way down, in the tower room, her fears cast from windows in retrospect. She could simply say to herself that she had unlocked the twelve sturdy locks, and removed the bar, and raised the miniature portcullis that led to the tower chamber, where it—the Insect—was contained.

And I could, she told herself, watch as the whole, fragile construct collapses to dust. While God—excuse me, Creator knows—what havoc the Insect is wreaking in the restaurant.

So, meticulously, Ann went window to window, tossing cloth packages and poisonous apples and broken daggers and twisted candles from her bag, until it was empty, and then removed the key ring, and set to work on the door. And then, free of all burdens, she stepped inside—to the tower room.

“Do you see it there?”

“I don’t.” The chamber was a circular tower room, with a single window overlooking a bright kingdom, far, far below. There was a chair. A table. A little flask of iced mint tea (in the past, matters had gotten uncontrollable when there was wine in the room). It was otherwise a bit of a cliché: but what was to be done about it? They’d devised it during the depths of Ann’s teenaged Dungeons & Dragons obsession. And circular tower rooms in wizards’ castles, as Ann had explained seriously at the time, were both pretty comfortable safe places, and made awfully good prisons.

Good, but obviously not perfect.

“It’s gone. It’s escaped.”

“Look up, dear.”

“Of course.” She looked up, into the rafters of this room—where just a few years ago, during the big blackout, when she was sure the thing had gotten out again, running amok in the dark corridors of her residence, flinging knives, she’d found it hanging like a great chrysalis, grinning down at her, long hair dangling like the tentacles of a man-o-war.

Not this time, though.

“Not this time,” said Ann.

“Keep at peace,” said Eva. “All right dear, let me tune in.”

Ann couldn’t help imagining Eva in the Wal-Mart, moving her hands so they hovered inches apart from one another, eyelids fluttering . . . the little rituals that she invoked, to tune in to Ann, and her safe place, and the prisoner that she kept there.

Imagining Eva in Wal-Mart, or indeed anywhere but in the circular tower room, was of course exactly the wrong thing to do. The safe place was an unreliable construct . . . a lie, really, although best not to think of it in those terms. Hurrying would knock it over, and so would distraction. Start thinking of some other place, particularly a real place (like the Wal-Mart) and that place intrudes.

“Stupid,” she hissed, as the door to the stall farthest from the door slammed shut and her eyes opened. “Sorry,” she said to the closed stall door. The woman who’d presumably gone inside didn’t answer, and suddenly Ann felt nothing but foolish—imagining how she must have appeared to the woman now sequestered in the stall, a moment earlier quietly passing the sinks, and wondering: what a strange young woman, leaning over the sink with her eyes shut tight. Some of us can’t hold our liquor. That’s what she would think.

“Ann?” said Eva, and Ann said, again: “Sorry.” She shut her eyes, and reassembled the tower room, re-inhabited it. “Got distracted.”

“All right,” said Eva, “now hush. I’m sending you energy.”

Indeed, as Eva said this, the tower room flooded with light—appearing through the mortar between the stones, and the narrow slit-like windows that gave a tantalizing view of the realm. Ann thought she’d have a look at that realm—cement some details in her mind—the bucolic roll of hills, a silver river that wended between them . . . that mysterious, snow-capped mountain range in the distance—and take in the energy that Eva insisted she was sending her.

Was she really? Sending energy? From Wal-Mart?

Questions such as those, Ann had long ago learned to suppress. And she did so now. After all, they did nothing to help her take control, to give her the strength she would need to wrestle the Insect.

A clank, as the door to the stall rattled. And a voice—echoing off the tile of the washroom. “Are you all right out there?”

“Fine,” said Ann, keeping her eyes shut this time, “thank you. I just need a moment.”

“Don’t we all.”

The hollow rumble of toilet paper unwinding now.

“You know what you really need?”

Still unwinding.

“I’m fine,” said Ann, while on the phone, from Wal-Mart, Eva said: “Shh.”

“That fine-looking young man out there. He’s a crackerjack!”

The door to the stall rattled fiercely. It slammed open, and closed again, and somehow Ann was turned around, the cell phone on the floor. Watching as the door to the stall slowly rebounded open. Showing nothing but an empty stall, with a long line of toilet paper, draped over the toilet bowl in a mandala form.

From the floor, Eva’s voice buzzed. Like a bug, Ann thought crazily (like an insect) and she watched, transfixed, as the silver button on the side of the tank depressed, and the toilet began to flush.

“I am satisfied,” said the Insect, as it settled back into its chair in the shadowy part of the tower room, crossing its hands on its lap, slender fingers twitching and intertwining. “I approve.”

“Thank you,” said Ann when she’d collected her phone from the floor.

“Did that do the trick dear?” asked Eva, from Wal-Mart.

“That seemed to do it,” said Ann.

“You sure now?”

“Sure,” she said—not sure at all.

Eva sighed. “I’m glad, dear. Be at peace. Now you call, if—”

“I will.”

From one tower to another, Ann LeSage made her way back. She could find no evidence of mayhem en route. The glasses hanging over the bar gleamed in the afternoon sun, which shone through windows clean and clear. The traders gesticulated at their tables, hands unblemished, while their cutlery stayed safe in front of them. The waiter was cheerful and intact behind the bar, tapping lunch orders on a computer screen. And Michael sat back in his chair, ankles crossed, hands palm-down on the table, while the saltshaker sat unmoving between them. His face was strangely, beatifically calm.

When Ann recalled that July day—months later, outside Ian Rickhardt’s Niagara vineyard, while she cradled an unreleased Gewürztraminer on the south-facing veranda and looked down upon the rows of grapevines, with just a moment to herself before their other guests arrived . . . this moment, not any prior or subsequent, was the moment that defined it. She, folding her skirt beneath her as she resumed her seat; Michael, looking steadily at her, unblinking, as he lifted one hand, and lowered it on top of the saltshaker like a cage of fingers.

“Gotcha,” Michael said as he lifted the shaker off the table and studied it with real glee.

Was it terror she felt looking at him then?

Was it love?

Love, she guessed.

Yes. Love.

iii

To say that Ian Rickhardt played a large role in the planning of their wedding was like saying the sun was a bit of a player in the solar system. The old man threw the wedding—planned it and drew up the guest list and staged it, taking things over and riding them all like a bride’s nightmare mother.

When Michael had told her about him, Ann thought Rickhardt might have been a father figure, standing in for the angry Afrikaner Voors. Michael had met Rickhardt in South Africa, over a rather complicated real estate deal. Rickhardt, who’d made his fortune in deals like this, saw something in Michael—clearly—and over the course of the years took an interest in the young South African. “He encouraged me to be my own man . . . eventually, to come here, and make my own life.”

Ann nodded to herself. Like a father, like a father should be.

When she eventually met Ian, for dinner one August Sunday at Michael’s condo, she scratched that idea too. He was more of an uncle.

He was near to sixty, but in fine shape for it. Had all his hair, which had gone white long ago and hung in neat bangs an inch above his eyebrows. He was lean without being gaunt, with a thin brush-cut of beard over a regular jawline. His eyes were pale blue and his skin a healthy pink.

Ian came to dinner in a pair of faded old Levis, and a motorcycle jacket over a black T-shirt. A wedding band, of plain gold, bound a thick-knuckled finger. His socks had holes in them, and he displayed them like hunting scars.

“The house at the winery is ancient,” he said. “Century house and then some. Very romantic, oh yes. Floors are the original oak, and they’re fucking stunning. But they spit up nails like land mines. The socks put up with a lot.”

Michael laughed at his joke and so did Ann—not because it was funny, but because it cut the tension that ran just beneath the surface of this casual little dinner party.

Because of course, it was barely a party, and anything but casual. Ann figured it out even as it began.

She was being interviewed.

So they sat down to a meal of lamb and collard that Ann and Michael had prepared together, with a bottle of Rickhardt’s cab franc, and as the sunlight climbed the bricks of Michael’s east wall, Ian genially put Ann through her paces.

“You are an orphan?” he asked as he poured wine into their glasses.

Deep breath: “My parents died when I was fourteen.”

“Car accident, I understand.”

“Yes. I was very lucky. But my mother and father didn’t survive.”

Rickhardt made a sympathetic noise as he sat back down. He gave her a look that said, Go on. . . .

“My brother—”

“—Philip.”

“—it was Christmas.”

“Michael was telling me. You two were very close, I understand?”

“I don’t think of him in the past tense. Philip survived.”

Ian nodded. “But not whole.” He took a sip of his wine. “That’s very hard, Ann. I’m sorry. And you’ve really been on your own since then.”

She sipped at her own wine. It was really very good.

“No one’s really on their own,” she said.

“That’s not always true,” he said. “But it’s lucky you haven’t been. And now you’ve met Michael, and that’s fine. You two are getting married.”

Needless to say, when Rickhardt arrived, he’d demanded to see the ring Michael had bought her and Ann obliged: a two carat emerald-cut diamond, set in a smooth band of platinum. Yes, they were getting married.

“I think marriage is good,” he went on. “Good for Michael, good for you. I wish my wife could be here. She’d like you.”

Michael nodded.

“What’s her name?”

“Susan,” he said.

“Sorry she couldn’t come,” said Ann. “I’d love to meet her.”

Rickhardt made a small smile and sipped his wine. “You’re young,” he said. “How young?”

Another sip of wine, all around.

“Twenty-six,” she said.

He nodded. “Michael’s ten years older. Practically an old man. That doesn’t bother you?”

Michael met her eye and smiled a little, shook his head, and Ann said: “Horrifies me, actually,” and Rickhardt laughed.

“She’s not in it for the money,” said Michael, and stage-whispered: “Don’t worry. She’s loaded.”

They didn’t really talk about money after that, although Rickhardt did ask her about her job at Krenk & Partners. He knew more than a little about them; Alex Krenk himself had joined forces with him in the 1990s, on an office development in Vancouver that had gotten some attention. Rickhardt had hired Krenk on various projects off and on since. They’d been asked to bid on designs for the restaurant and retail structures at his vineyard but had fallen short.

He told this story with clear expectation that Ann might jump in, but it was difficult. She was junior enough at the firm that she had no real knowledge about the Vancouver development; she’d helped out on some of the design for the vineyard, though, and she mentioned that. Rickhardt managed to say something nice about the bid, but facts were facts: the bid had fallen short. Ann attributed his words to a belated attempt at basic good manners.

There had been no mistaking when he’d finished his interview with Ann. He asked her a question about the type of care Philip was getting, but he clearly wasn’t interested. Halfway through her answer, he was refilling his glass.

She was in the middle of a sentence when he looked up, right past her, and asked Michael, “Hey, do you remember Villier?”

Michael frowned, snapped his fingers, and said, “John Villier? From Montreal? Of course! What’s he up to?” And so they launched into a long, context-free reminiscence about a trip the three of them had taken somewhere, some time ago, involving a seaplane and a great deal of liquor.

After Rickhardt left, they fought.

“He’s a jerk,” Ann said. They were standing on the narrow balcony where it overlooked the reclaimed industrial lands of the city’s east end. Across the street, patrons from a café built from an old auto body shop sat under glowing orange lanterns and wide umbrellas outside the open garage door, getting happily buzzed before another work week.

“That’s not fair,” said Michael, his voice taking a plaintive edge. “Ian’s just of a different generation.”

“Fair enough,” she said. “What’s your excuse?”

They’d both had some wine by then, and Ann’s tone was sharper than she’d intended. Two glasses ago, she might have stopped herself from pressing the matter.

“You left me out to dry,” she said. “Ian Rickhardt treated me like a piece of property, a new car you brought home. He came over to check it out. Check me out.”

Michael tucked his chin down, put both hands on the balcony rail, and pretended to study the seventh-day revellers in the café. “That’s not what was happening,” he said.

“Wasn’t it?”

“I told you he could be a little off-putting.”

“Yes. You did. And it was off-putting. So off-putting you

abandoned me.” Michael stepped back from the railing and held his hands in the

air, a gesture of retreat. He stepped back through the doors and retreated further, to the kitchen. Ann looked away from him, down at the café. As she watched, one string of lanterns flickered, and went dark.

Good, she thought, and was immediately ashamed.

Now, at the vineyard, staring out at the stand of fiery golden maple trees, watching the van make its way up the drive, and wondering if there might be some more of that delicious Gewürzt inside, Ann winced at the memory. She swilled down the last dregs of the wine from her glass, and drew a deep breath of the smell of this place—woodsmoke and loam—and turned to go back inside Rickhardt’s winery. This was the place that Krenk & Partners didn’t design, and from the look of it, wouldn’t have if they’d been asked: all glass and oak around the tasting bar, faux-Bavarian beams demarking a first-storey ceiling below a dark loft above, railing hung with evenmore-faux grapevine. Home Depot had won that bid, no question.

Rickhardt is a jerk. Also no question.

Ann swung around the tasting bar and pulled the half-empty bottle of Gewürzt out of the cooler. She poured herself half a glass.

He was a jerk. But so was she. She realized it when later that August Sunday, she’d come inside and started drying the dishes Michael was washing, and Michael had told her: “He wants to pay for the wedding. That’s why he wanted to meet you. He thinks of me as a son. I’m sorry you didn’t hit it off.”

Ann took a sip, and then another. She started to take a third, but stopped herself as the wine touched her lip and set the glass down on the bar. The place would fill up in just a few hours with the guests at her Ian-Rickhardt-Productions wedding. From the sound of things, it was already starting.

Outside, she could hear the van pulling up. For a moment, she considered finishing the wine. But she resisted.

There would be plenty of time for wine later.

iv

Ian Rickhardt’s list of guests was longest, at seventy-seven; Michael Voors’ list less so but still respectable at twenty-six. Ann LeSage invited just five people to her wedding and Ian and Michael both looked worried. But she insisted it wasn’t so sad as that. She loved four of them, and she was sure they loved her too, and that counted for a great deal.

Jeanie Yang had been Ann’s roommate for two years at the University of Toronto, and together they had explored the delicate art of old-school pencil-and-paper role-playing games, the subtle art of Anime, and the numbing craft of single malt scotch. She was working across the border in a lab outside Chicago, but caught up with Ann in G-chat as soon as she got the invite and said she’d drive out.

ANN: It’s a long drive.

JEANIE: OMFG its not. im a midwestrn grl now. everywhere goods 5 hours drive.

will lesley be there?

ANN: ummmm

JEANIE: :p

It was not awkward in the least, Jeanie insisted, that also attending would be Lesley Chalmers—another member of their little circle, with whom Jeanie had shared a bed for a semester. Lesley was in the architecture program with Ann, which was how she had met Jeanie, and it had been a terrible drama that year, Ann mediating their courtship, affair, and breakup.

Lesley was in Toronto, still; in school, still. She and her partner, Bec, would rent a car and make a weekend of it. Lesley was oldfashioned. She confirmed by telephone.

“Who’s going to be your maid of honour?” she asked.

“It’s awful, but I haven’t really picked one.”

“Wow. And the wedding’s—when?”

“October.”

“This October.”

“That’s right.”

“You know it’s already September, right?”

“I suppose I should pick one.”

“I suppose you should,” said Lesley. “It’s awfully last minute. It would have to be a very good friend.”

Ann stifled a laugh. Sometimes, the time since graduation seemed like a lifetime. Sometimes, like no time at all.

“Lesley,” she said, “would you do me the honour?”

“Given it a lot of thought, have you?”

“A lot.”

“Do I have to buy a lime green dress with shoulder ruffles and a big fucking pink bow on my ass?”

“Yes.”

“Does Jeanie have to wear one?”

“No.”

Quiet on the line, then: “She’s invited, right?”

Sometimes, it was like no time at all had passed. Ann reassured her friend that all was well with Jeanie, and fielded a few questions about how she was doing, and explained that yes, Lesley was maid of honour because Ann liked Lesley better and had secretly taken her side in every dispute—and agreed with her that Jeanie would not look as good in lime green and pink as Lesley, and would be madly jealous when she saw her, teetering on those stripper heels through the Chicken Dance.

Ann did not ask Lesley if she had asked about Jeanie because she was still hung up on her . . . if it would have really been better if one or the other of them hadn’t been invited. In return, Lesley did not ask Ann about the quickness of the marriage, and if she mightn’t have jumped into it less from the dictates of desperate soul-searing love, and more as a consequence of her general isolation from the world; if her minuscule guest list might not indicate a more dangerous isolation, for a young woman set to marry a wealthy lawyer she’d only known for a few months.

Questions like those were best left to Eva Fenshaw.

Eva booked into a bed and breakfast in the little village of Vanderville on the Bench almost a week before the wedding.

What the hell? Ann wondered.

But Eva said she could afford it, and she loved the fall colours, and she wanted to be well-rested for the celebrations. And she didn’t want to be any trouble for the Rickhardts at their fancy winemakers’ house, which was where Ann and Michael were staying.

“I know I’m welcome,” said Eva before Ann could say it herself. “But I’m more comfortable here.”

When she drove out to see her, Ann admitted she could see how. The bed and breakfast was a two-storey, red brick, pinkgabled Victorian, just off Vanderville’s miniscule downtown. A chestnut tree shaded a big garden, still lush in the early autumn with nasturtiums overflowing clay pots and poking between field stone and little concrete gargoyles, still-flowering stalks of zabrina mallow growing everywhere. Its owner was a woman who might have been Eva’s baby sister: a menopausal earth-mom in peasant skirt and T-shirt decorated with the Mayan alphabet.

The ground floor was filled with crafty knickknacks that somewhat-less-than-casually suggested Christmas. Yes, Eva said when they settled down for lunch at Stacey’s, a diner on the town’s main strip—not five minutes from the B & B—her bedroom followed the festive theme.

“It’s like sleeping in a Christmas window display,” she said. “Quite some fun, actually, if you’re open to it.”

“If you say so.”

“I say so.” Eva smiled, and Ann smiled back. Although they spoke very regularly, they didn’t see each other in person much anymore, and that fact hit home with Ann as they sat there. Eva had aged visibly since they’d last had a meal together, a year or so ago; gained some weight, bent a bit here and there . . . her light brown bob was more grey. When Ann looked at her, she remembered her from a decade ago, taller, more tanned, not more than a wisp of grey in hair that went to her shoulders, telling Ann and her Nan about Tibet. The intervening years hung from her like debris.

“Thank you for coming,” Ann said. “It means a lot to us.”

“Oh, don’t say that.” Eva shook her head. “‘It means a lot.’ What’s ‘a lot’? A lot of what? A lot of hooey.”

“It’s something people say,” said Ann, knowing even as she spoke the direction the discussion would take, and so was utterly unsurprised when Eva said, “People hide behind words like that. They don’t say what they mean and then it’s all lies. Not that I’m calling you a liar.”

“Of course not.”

“And yet . . .” Eva lifted up the menu and read from it: “Chinese and Canadian Food. Do you suppose they have poutine?” She scanned down with a fingertip. “Oh they do!”

“That takes care of the Canadian part,” said Ann.

“I think I’ll have poutine. Imagine, living here all my life—and I’ve never had it before.”

“You’re on your own,” said Ann.

Eva clucked her tongue. “I wonder if they have herbal tea here? All it says is tea.”

“Should I ask?”

“I can ask.” Eva shut her menu, and signalled the waitress she was ready.

“Now tell me about this ceremony we’re having on Saturday,” said Eva after confirming that there was indeed herbal tea available, and that yes, the poutine was “any good.” “You’ve got your wedding dress. I bet you look lovely in it.”

“I do,” said Ann. She took her phone out of her purse and showed Eva pictures on the tiny screen.

“Wow,” said Eva as she flicked through the images. “You’re a beautiful girl. Your Nan would be so—”

Ann put her hand on Eva’s and gave it a squeeze and Eva squeezed back. Eva and her Nan had come to be good friends before she died. Almost as good friends as Eva’d become with Ann in that time.

“So proud,” said Eva. “You’re getting married.”

“So I am.”

“Are you sure?” Eva looked at Ann levelly. She had been smiling

the whole time, but now it faded. “It’s very soon.”

“Sometimes you know,” said Ann.

“That’s true,” said Eva. And as the steaming plate of fries, cheese curds and gravy arrived: “Michael is a nice fellow.”

“I’m glad you like him.”

Eva stabbed a french fry with her fork. She sniffed it. “You think I don’t like him,” she said, watching with fascination as a string of melted cheese curd snapped off the bottom of the fry.

“I—” began Ann, but Eva kept going.

“You think I’m coming here to bust this up, don’t you?”

Ann opened her mouth and closed it again. Yes, she had to admit, deep down she did think that. Eva didn’t like to travel. She didn’t like to sleep away from home. Ann had idly wondered if Eva wasn’t coming to town early to set up her B & B room as a kind of base camp for a more intensive campaign.

Eva squinted, popped the fry in her mouth and nodded as she chewed it.

“You know, we used to talk. A lot more. You’d tell me everything. And I’d tell you everything too. And when I said I thought somebody was a nice fellow, it was because I meant it. And I mean it now. Michael Voors is a nice man.”

“For a lawyer?” asked Ann.

Eva shrugged. “Can’t say I’ve known very many,” she said, and her smile broke out again, and they both laughed.

“You’re taking a step in your life,” continued Eva. “You’re taking it more quickly than we would have, when I was your age. . . . My God—Creator—that’s an awful thing to hear yourself say. . . . But it’s a good step all the same. I’d be more worried if we were sitting here five years from now, and you hadn’t taken any kind of step—that’s an awful thing to say too, because there’s nothing wrong with being independent either.” She put her fork through a clot of gravy and starch and twisted it like it was spaghetti. “But you know what I mean.”

“I don’t really have any idea,” said Ann.

“Only this,” said Eva. “You’ve got my blessing. Michael . . . He is a nice man. I can tell, you know. And you . . . If you’ve got any doubts or second thoughts . . . Well, like you said, sometimes you know. I don’t think you really have doubts, now do you?”

She raised her eyebrow, and Ann said, “I don’t. No.”

Eva nodded, and leaned in forward, a little confidentially. “And he is a handsome young man. I assume he’s good . . . you know.”

“Eva!”

“Oh, I’m not a prude,” said Eva, laughing. “Don’t you be. Sex is important. It’s part of a marriage.”

Ann didn’t know what to say. Sex was important. And it was . . . fine with Michael, she guessed. Not great . . . not as frequent as she’d have thought. Something, she’d supposed, they could work on, on the honeymoon.

“Don’t worry, Eva,” she said. “Michael keeps me more than satisfied.” She made a show of winking. “If you know what I mean.”

Eva nodded again, and this time had the good grace to blush—at least a little. “Well good,” she said, and they sat quietly.

Ann had ordered a grilled chicken sandwich. The waitress came with it, finally.

“I had a dream about you last night,” said Eva when the waitress had gone. “Very vivid. I think it might have been the new place I was sleeping; all that Christmas stuff. It was a good dream.”

“Oh?”

“It was at the house by the lake,” she said. “Before . . . well, before it sold. We were all younger—your Nan was there. It was Easter I think, because I remember a basket of eggs on the dining room table. You weren’t actually in the room. . . .”

“That’s not surprising,” said Ann. “I didn’t go back there once during the time you knew me.”

“Oh, I know, believe me. That was the last place you should have been, then,” said Eva. “Your Nan and I sometimes went back there. Particularly as it was getting ready to go on the market.”

“You didn’t tell me.”

“She didn’t want to be there alone. I didn’t want her to, either.” Eva paused for another bite of poutine. “We had good talks there.”

“So it wasn’t really about me.”

“We were talking about you. You were going off to a new school in the fall—a private school. Your Nan thought it would be good for you.”

“I probably hadn’t studied for the exam,” said Ann. “That’s how my dreams about going off to school usually end up.”

“This wasn’t going to be like that.”

“You could tell that?”

“She knew you could do it.”

“Of course she—” Ann stopped and swallowed. Eva sat quiet, waiting. But Ann didn’t cry. Outside the window, a truck pulled by, gears grumbling as it crawled down the street.

“The marriage is a good thing,” said Eva. “Michael—he’s lost his family too, really. They’ve driven him off, it’s the same thing. So it’s no surprise that you want to make a new one quickly, now that you’ve found each other. And you must be feeling pretty secure in each other. In everything.” She punctuated with a raised eyebrow.

Ann raised both, to say: Go on, Eva.

And Eva went on: “I mean to say, if you weren’t secure—if you didn’t feel really safe . . . you never would have invited him.”

The van had pasted on its side a photograph of trees, blue sky— across its tail, hands joined together, pale as clouds. MARGARET HOLLINGSWORTH RESIDENTIAL CARE, written in fine script. If you passed it on the highway, you might mistake it for a minibus— something that would carry residents well enough for day outings to the nearby mall. Stuck in traffic, you might notice some other things about it—the reflective shades drawn down over the windows; the eighteen-inch caduceus stencilled above the license plates . . . the small blue light on the roof.

While it was true that the Hollingsworth Centre had those other kinds of buses, the ones for the mobile residents—this one wasn’t one of those.

Ann knew about this kind of bus. Point of fact, she knew this one. Ann recognized the attendants, although she couldn’t remember their names: the woman had short brown hair and a deep tan, she liked to snowboard; the man was black-haired and balding. He waved at Ann where she stood hesitating on the ramp to the winery, and jogged across the drive while the woman (Ellen? Alana?) opened the tailgate of the van and manoeuvred the hydraulic lift into place.

“Hey there!” said Ann, and squinted at the name tag, and (when he was near enough) finished: “Paul.”

“Hi, Ann.” He stopped and put a hand on the railing, looked around and nodded—taking in the grounds. “This is a beautiful spot. This where it’s going to be?”

“This is it.” Ann spread her arms as if to indicate the world. “Ceremony and reception.”

“Very nice.” He regarded the ramp and nodded again. “Elaine—” (Aha! Elaine!) “—is getting him ready.”

“Was the trip okay for him?”

“Very comfortable. Traffic was smooth, so we made good time; he didn’t need anything until the last leg. So he’ll be a little sluggish now. But trust me—he’s in great spirits.”

Ann sighed. “That’s good,” she said, in a way that was apparently unconvincing.

Paul suddenly became very earnest. “Ann—it is good. He’s very excited to be here for you today. He called this his ‘road trip.’ He’s been cracking wise about dancing at your wedding all week.”

Ann laughed—more convincingly this time. That being the kind of gag she’d have expected, from him.

Paul stepped back from the railing and beckoned her back to the van.

“Let’s go say hello,” he said. “I’ve got to help with this next part.”

“Let’s,” said Ann. And she smoothed her skirt, and crossed the drive to the van.

“Hi Ann!” said Elaine, poking her head out of the back of the van. “Do you want to come up inside before we send him on his way?”

Ann peered inside. The interior of the Hollingsworth minibuses were well enough lit for their purposes; but in the afternoon light, the compartment looked like a black pit. She swallowed, and drew a breath, and said: “I don’t want to get in your way.”

“Okay,” said Elaine. “Paul, give me a hand?”

And when Paul turned away, and it was clear no one was looking, Ann shut her eyes.

She was in the corridor. Sunlight streamed in through the tall windows facing the east. At the end of it, in a deep shadow, the ironclad door stood still. Ann walked carefully down the hallway, not tossing anything out this time, until she could lay a hand on the door, run her fingers over the cool iron locks and bolts there. She pressed her ear against the wood, and listened.

Inside, it was silent.

Good, she thought. Stay that way.

She opened her eyes at the touch of a hand. “Hey,” said Elaine, “say hello.”

“Hi big brother,” said Ann, as the wheels of Philip LeSage’s chair rolled off the lift platform. She stepped closer, Elaine still holding her arm. Philip wore a green Roots sweatshirt that she remembered hugging his shoulders like a skin. Now, he was lost in it. His head lolled in its brace, and his lips pulled back over his teeth in the thing that he did these days to smile. His eyes blinked over hollow cheeks, under brown hair sheared competently, by the hand of a Hollingsworth nurse.

Hello little sister, came the whisper.

The ‘Geisters © David Nickle 2013